The Making of an Enemy: Viral Anti-Rohingya Propaganda in Myanmar and its Consequences

In the summer of 2017, the Burmese military began a systematic process of driving hundreds of thousands of native Rohingya people out of the Rakhine State in western Myanmar. This genocidal violence against the long-persecuted ethnic minority has been accompanied by viral cartoons and memes that cement anti-Rohingya notions in Burmese society. This exhibit explores the ways in which such propaganda has legitimized state violence against the Rohingya in the eyes of many Burmese citizens. Further, it analyzes the popular myths and tropes underlying these dangerous depictions of the ongoing Rohingya genocide.

In this image, a Rohingya militant uses civilians as human shields as he targets a Burmese soldier. The soldier is seen defending a woman and child, reinforcing the popular notion in Myanmar that the military is the Burmese public’s last line of defense against pathologically violent Rohingya “terrorists.” Like many other anti-Rohingya propaganda pieces, this scenario inverts the reality on the ground — where unarmed Rohingya civilians are being regularly targeted by Burmese soldiers and vigilantes.

This image also seems to conflate the Rohingya people with militant Salafi organizations such as Al-Qaeda and Da’esh (ISIS). The Rohingya people are a Muslim-majority ethnic group in Buddhist-majority Myanmar, which has been increasingly gripped by Buddhist extremism and supremacism. The above image is accordingly laced with Islamophobic depictions of Rohingyas as maniacal terrorists who use human shields and suicide bombs to achieve politico-religious aims. It also legitimizes the Burmese government’s false claims that anti-Rohingya crackdowns are merely anti-terrorism operations against ISIS-aligned rebels. At the core of this framing lies a dangerous false dichotomy: a “bad” Muslim minority led by terrorists, and a “good” Buddhist majority protected by a strong national military.

In another image popularized on social media, a Rohingya man assaults a Burmese civilian. The man deceitfully tweets out an alternative scenario in which he is the one being attacked by a Burmese soldier. This scenario reinforces a popular trope in Myanmar that the “real aggressors,” the Rohingya people, are using social media to manipulate global perceptions about the conflict.

The truth is that real images of Burmese military and vigilante violence against Rohingya civilians have gone viral around the world. Extrajudicial killings, arson attacks, mob violence, and other acts of anti-Rohingya terror have been documented by independent observers, as well as by Rohingya social media users themselves. Though some insurgents belonging to the Rohingya minority have indeed attacked state targets, such acts of resistance have taken place in the context of intense persecution. The Burmese military has tragically used these attacks as a pretext for wholesale acts of ethnic cleansing against the Rohingya people, particularly in the form of the genocidal “clearance operations” that began this past summer. In the months leading up to this, Myanmar pursued a sophisticated strategy of preparing Rohingya communities for decimation by arbitrarily arresting community leaders, working-age men, and religious personalities.

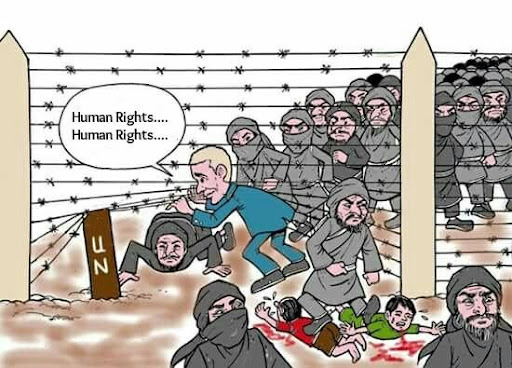

This comic relies on the trope that Rohingyas are dangerous foreigners seeking illegal entry into Myanmar with the assistance of the United Nations (UN). This “human rights” agenda is portrayed as leading to the deaths of Burmese children at the hand of the Rohingya people, depicted as violent mobs of masked Muslim men. The reality is that hundreds of thousands of defenseless Rohingya civilians have been forcibly pushed out of Myanmar in the past months, and many simply hope to return home. The UN’s role in the crisis has primarily been limited to the documentation of human rights abuses.

Though the de-facto Burmese leader Aung San Suu Kyi has offered vague assurances that some Rohingya refugees will be allowed return to Myanmar, a number of questions surrounding repatriation remain unanswered. For example: How will Rohingya returnees reclaim their land and crops, given that they have no land ownership rights under Burmese law? Will the “model villages” that the government intends to build for them simply be concentration camps? Will reparations ever be made to the former residents of the nearly 300 Rohingya villages that have been razed to the ground by the army and ethnic Rakhine Buddhist mobs?